White

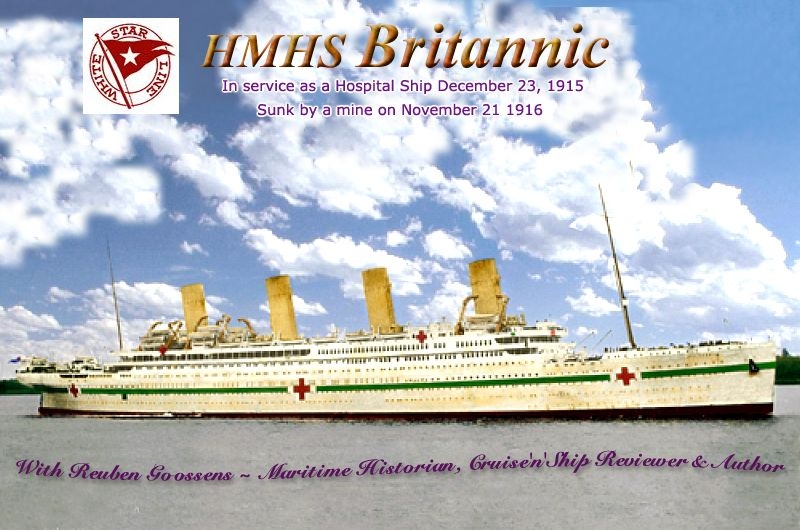

Star - ill-fated Hospital Ship the HMHS Britannic

Please Note: Firefox and

Google Chrome are

not suitable - Use Internet

Explorer & old Google for this page to load

perfectly!

Click the

logo above to reach the ssMaritime FrontPage for News Updates & “Ship

of the Month”

With

Reuben Goossens

Maritime

Historian, Cruise‘n’Ship Reviewer, Author & Maritime Lecturer

Please

Note: All ssMaritime and other related

maritime/cruise sites are 100% non-commercial and privately owned. Be assured

that I am NOT associated with any shipping or cruise companies or any

travel/cruise agencies or any other organisations! Although the author has been

in the passenger shipping industry since 1960, although is now retired but

having completed over 700 Classic Liners and

Cargo-Passengers Ships features I trust these will continue to provide classic

ship enthusiasts the information the are seeking, but above all a great deal of

pleasure!

Reuben Goossens.

Images

are mostly from the author’s private collection unless otherwise noted

A

special thank you to superb maritime artist Ken

Marschall for his works on this page, please visit his Website at www.trans-atlanticdesigns.com

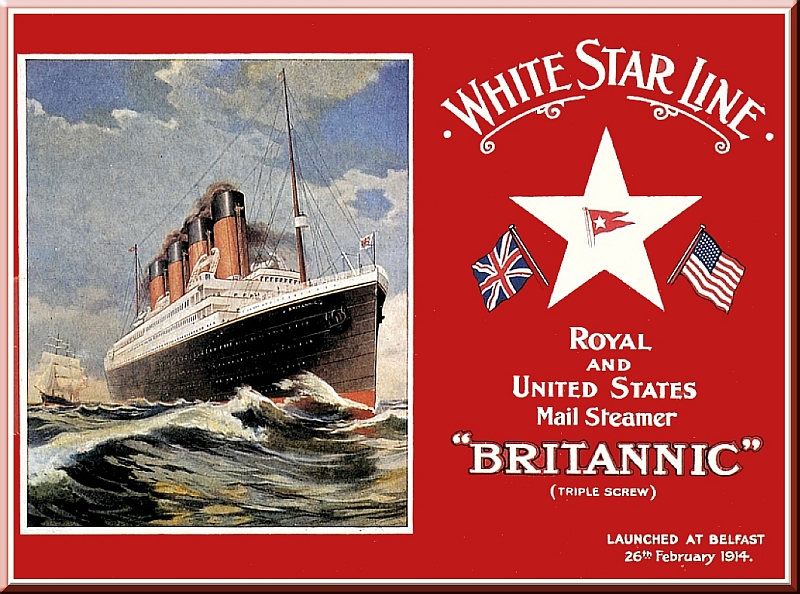

1… White Star Line:

The RMS Olympic was part of the

White Star Line and was owned by the British “Oceanic Steam Navigation

Company.” However, all of this company’s stock was owned by the

“International Navigation Company Ltd,” of England, which

in turn, was fully owned by the “International Mercantile Marine

Company” (IMMCO), which was an American Corporation.

Therefore White Star

Line and later Cunard Line may have been British operated, and Cunard still is

today, but in reality it is a wholly American owned company both then and now!

The only difference is that today Cunard Line is owned, by different American

company, being the Carnival corporation, or as most people know them to be -

Carnival Cruises, which is a massive company that now owns so many of the well-known

cruise brands, such as P&O Australia, P&O UK, Princess Cruises, Costa,

Aida and Seabourn Cruises, even the outstanding Dutch company Holland America

Line, and the list just goes on! Thus Carnival influences all these cruise

companies, and they are marketed by Carnival Plc!

2… Introduction to the Britannic:

The first of the Olympic Class

Trio to be built was of course the RMS Olympic, which turned out to be the only

liner of the three to have a long and successful life at sea and she was a much

loved ship by all that sailed on her, regardless the class they were in! The

RMS Titanic was as history has proven to be the ultimate disaster, and although

it was one of the most tragic of events with a huge loss of life, some good did

come out of it, as safety became more regulated. Very quickly both the Olympic

received a considerable refit with the strengthening of her hull and watertight

doors and other improvements, also a big change with additional lifeboats, and

thanks to the crew taking a tough stand on the collapsible lifeboats, they were

discarded and new ones obtained and far superior davits were installed, etc!

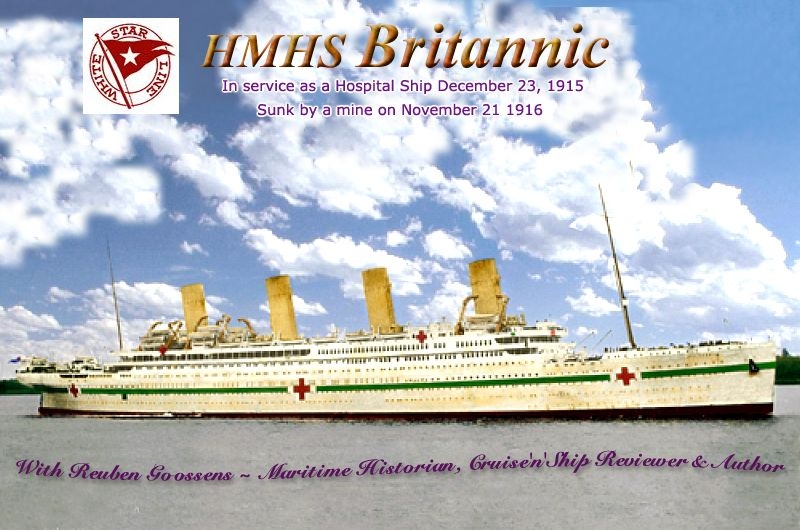

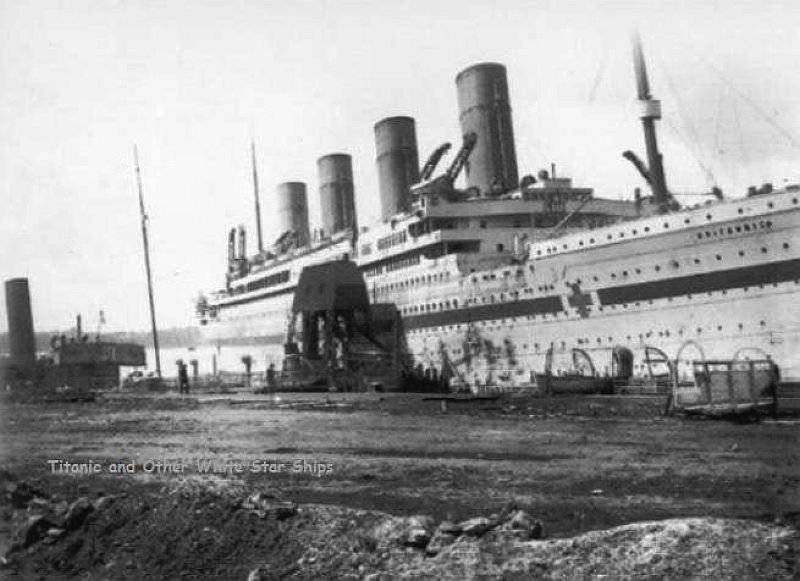

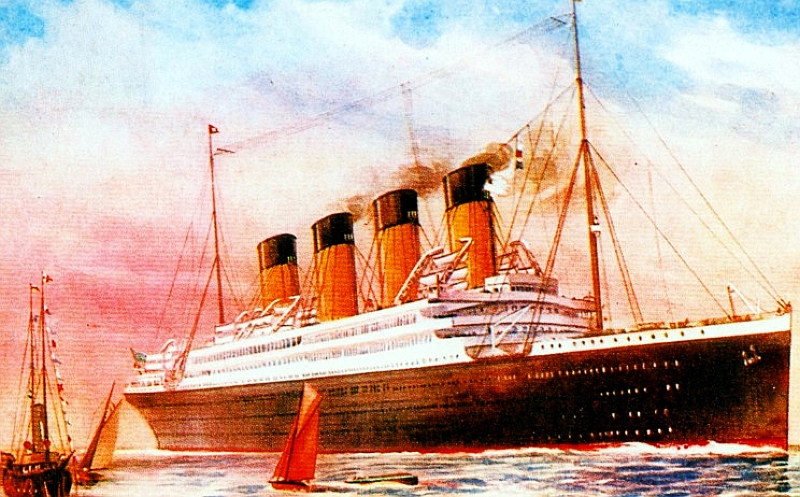

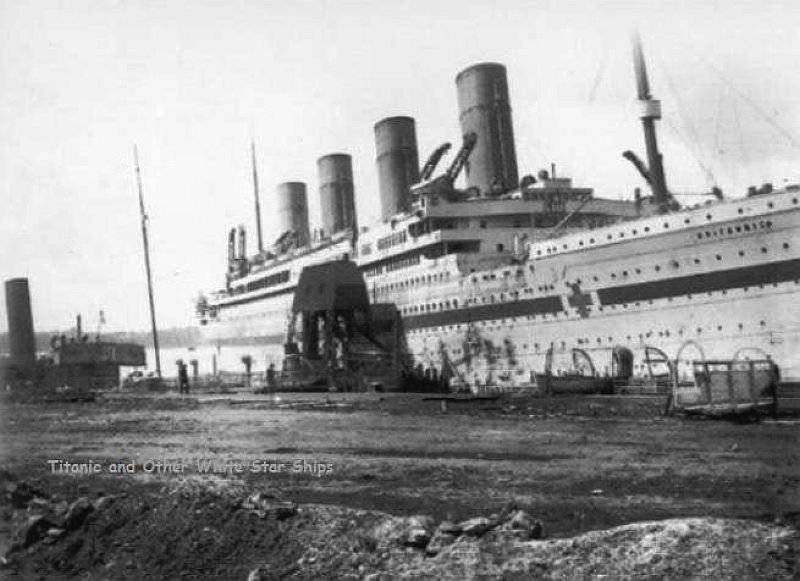

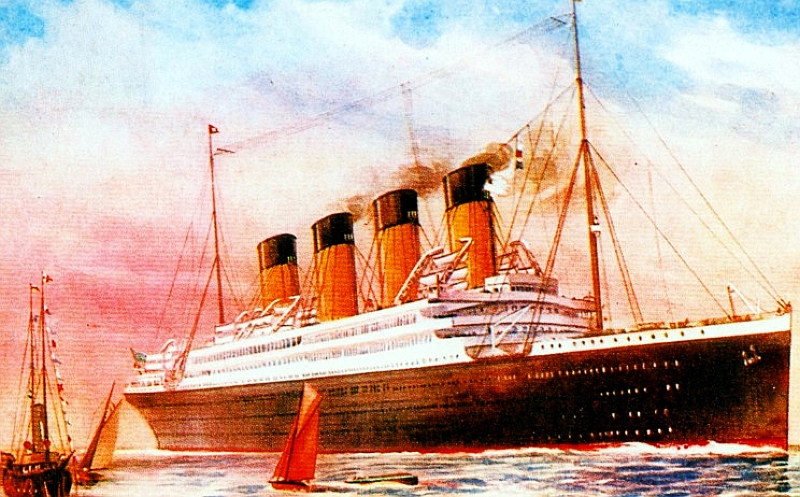

RMS

Britannic as she looked after she was completed and placed in storage in Belfast during the war,

before her call up

Note all the additional lifeboats

that she carried

Whist the building of the Britannic

was greatly delayed, which was due to the outcome of the court enquiry into the

Titanic disaster and due to the results of the enquiry many additional safety

features had to be added to the Britannic, even more than to the Olympic, which

was due to her having been built earlier and whilst this new ship was obviously

far more accessible!

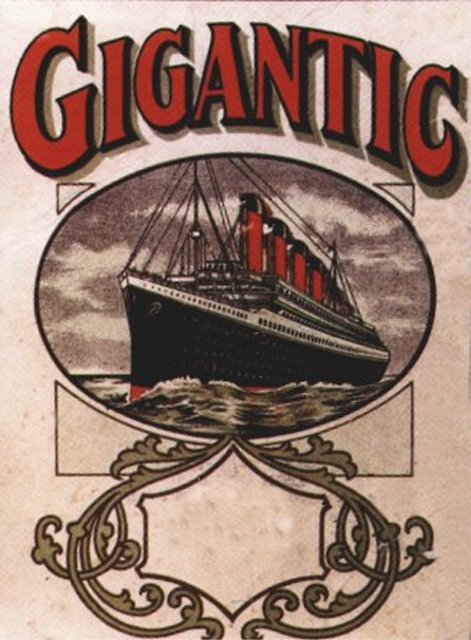

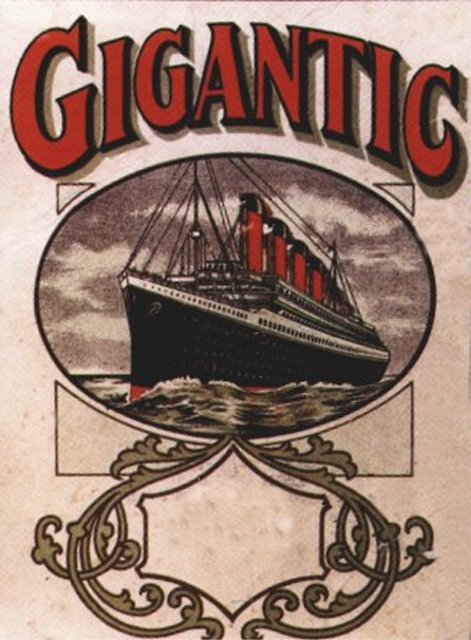

Gigantic

or Britannic?

It has always been said that the

third ship was to be named the Gigantic and the story goes as thus: Before the

Titanic disaster, she was to be named the Gigantic, a name which would seem to

be in keeping with her sister’s names. However, White Star Line later

denied that she was to be called Gigantic and that late in May 1912 it was

announced that she would be named Britannic, a name that was considered

“lucky” due to the superb career of their first Britannic.

I must say however, that the truth is that one

way or another that the above has never been fully proved or disproved for that

matter. But at some stage there was a poster printed in the 1900s that showed

her clearly as the “Gigantic”, but the question begs who printed

it, for it does not say “White Star Line.” Thus I will leave it

open-ended and for you to make up your own mind!

The

Britannic (Gigantic?) was the sister ship to the Olympic and Titanic, although

the three sisters never sailed on the North Atlantic

together

This, the third of the great White

Star Olympic class liners, the Britannic was also built by Harland & Wolff

in Belfast, in fact she was laid down in the very same yard the same slip where

Olympic had been built several years earlier. Laid down in November 1911, she

was extensively modified while still on the stocks to correct the fatal design

flaws that had contributed to Titanic's disaster. But, like her ill-fated

sister, Britannic was destined never to complete a single fare-carrying voyage

for her owner and, in fact, sank more quickly than Titanic even with her new

safety modifications.

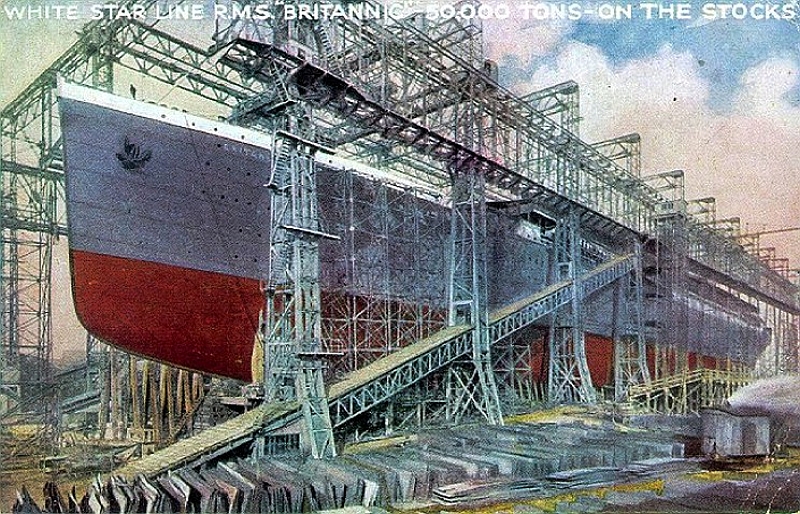

3… Construction and Launching of the

Britannic:

Britannic’s

keel was laid on November 30, 1911 at the Harland and Wolff shipyard in Belfast. But due to

improvements introduced as a consequence of the sinking and the massive loss of

life of the Titanic, the Britannic would not be launched until 1914.

She was constructed in the same gantry slip

(#400) that was used to build RMS Olympic, thus by reusing the Olympics’

space saved the shipyard time and money by not having to clear out a third slip

similar in size to those used for Olympic and Titanic. In August 1914, before

Britannic could commence transatlantic service between New

York and Southampton, the First

World War began. Immediately, all shipyards with Admiralty contracts were given

top priority to use available raw materials. All civil contracts, including the

Britannic, with good reason slowed down.

Construction

Photographs

Here

we see one of her decks laid and work continues to build the third of the

Olympic Class liners!

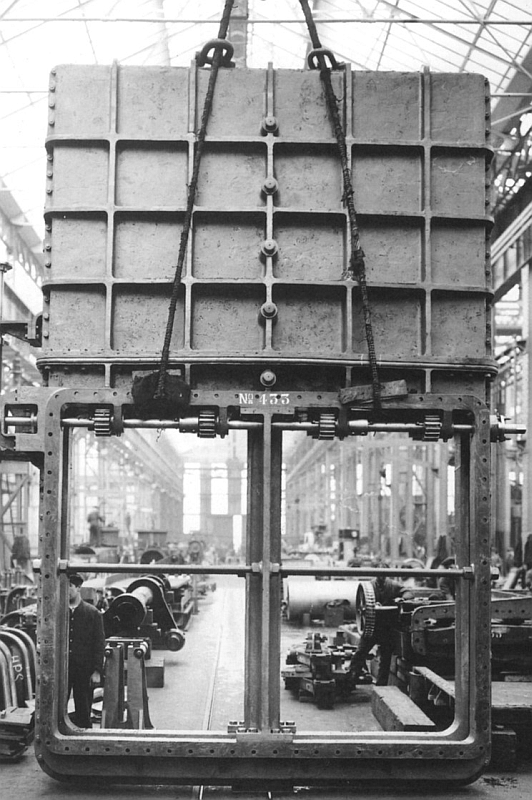

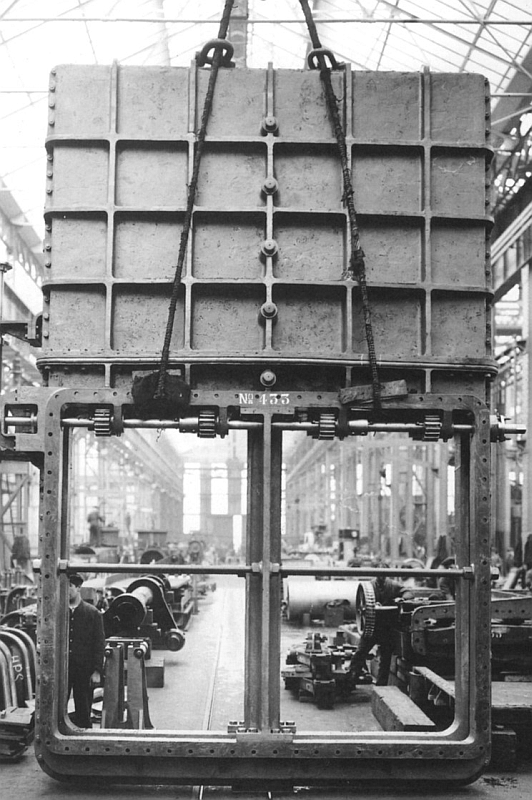

Here

we see one of her watertight doors

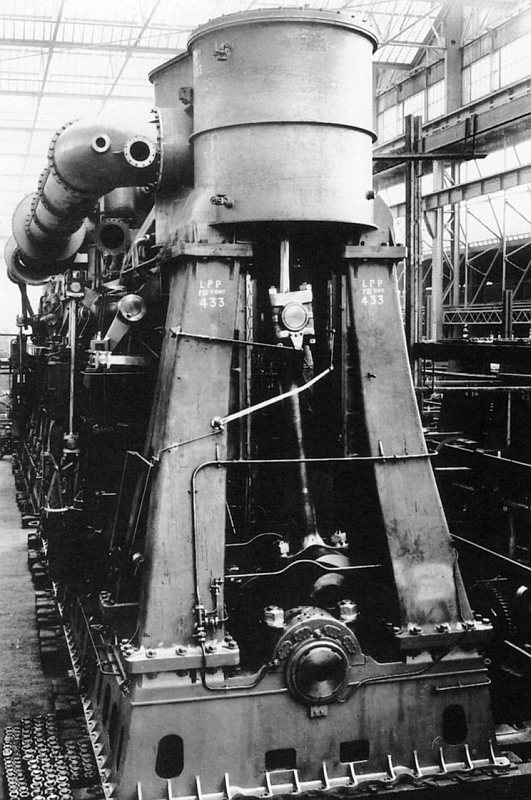

One

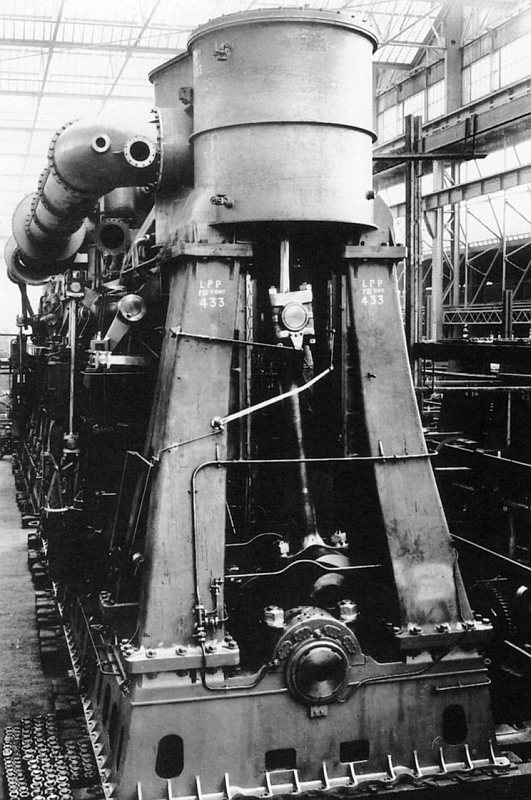

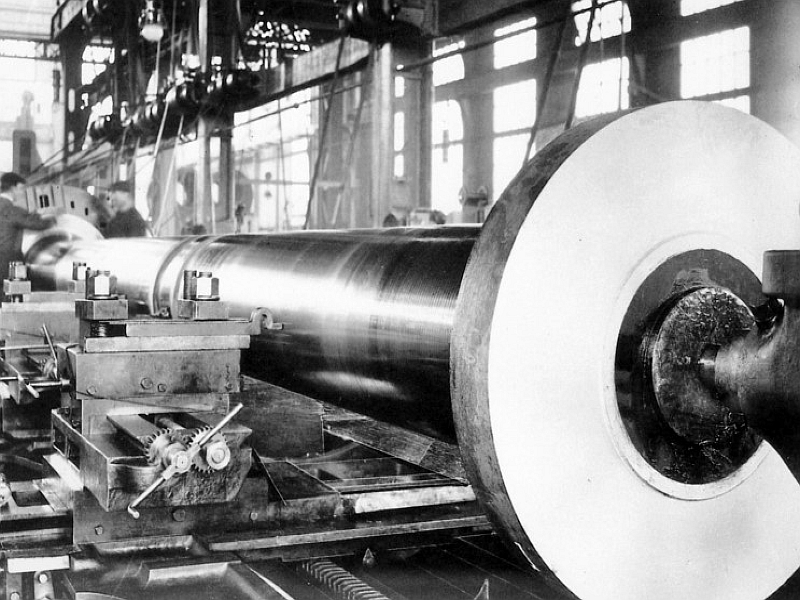

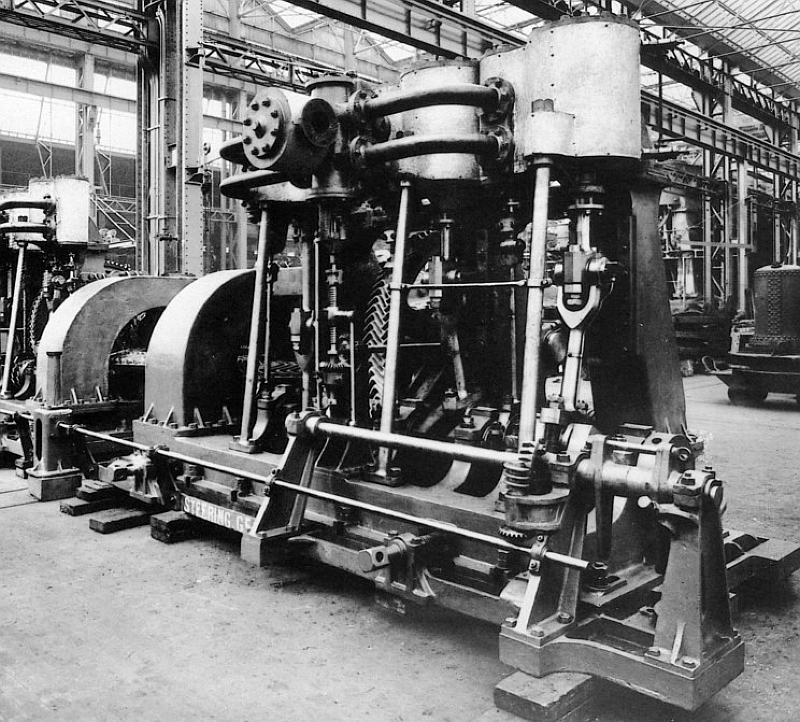

of Britannic's massive four cylinder triple expansion steam engines

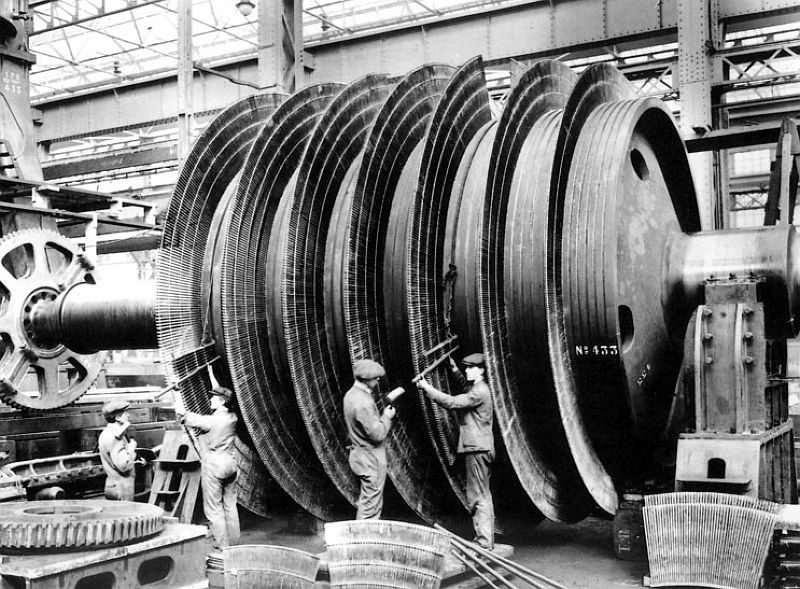

Here we

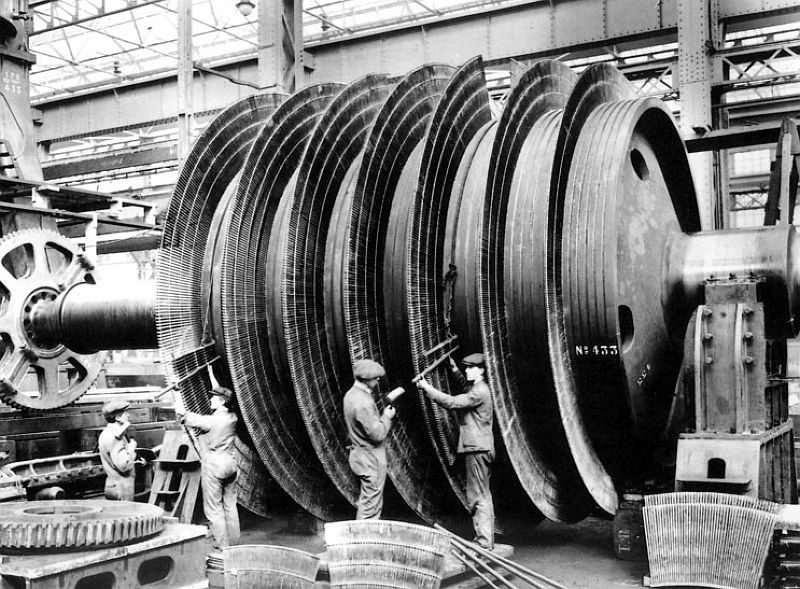

see her turbines being finished

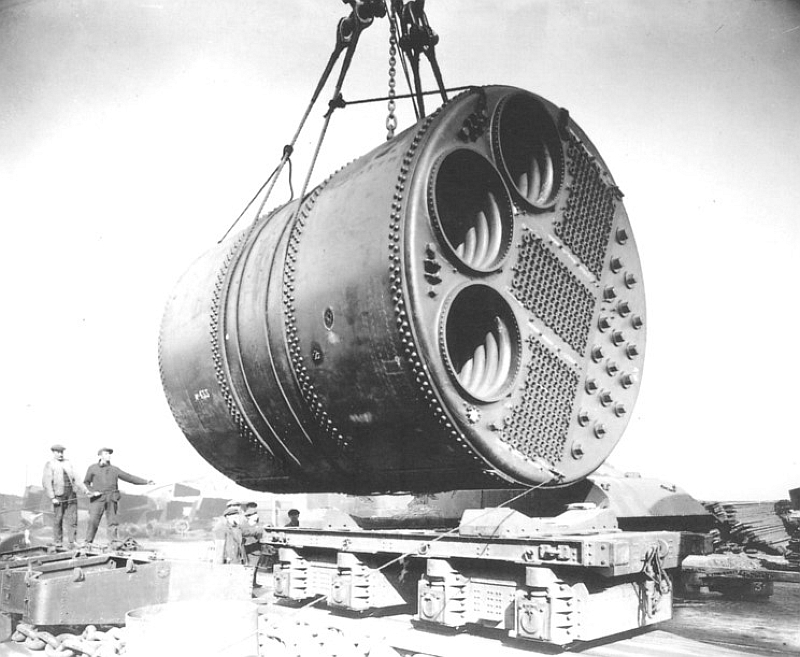

Here

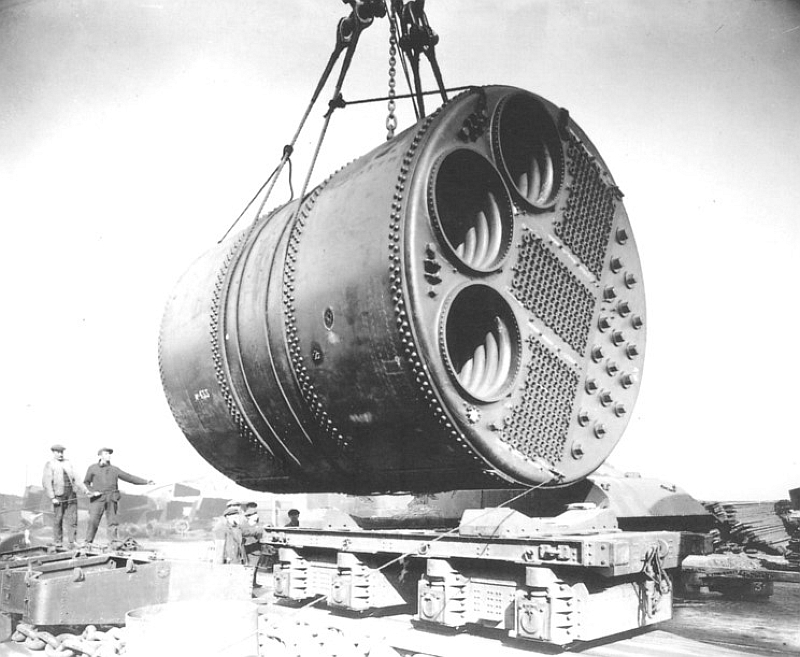

we see one of 24 double-ended boilers

This

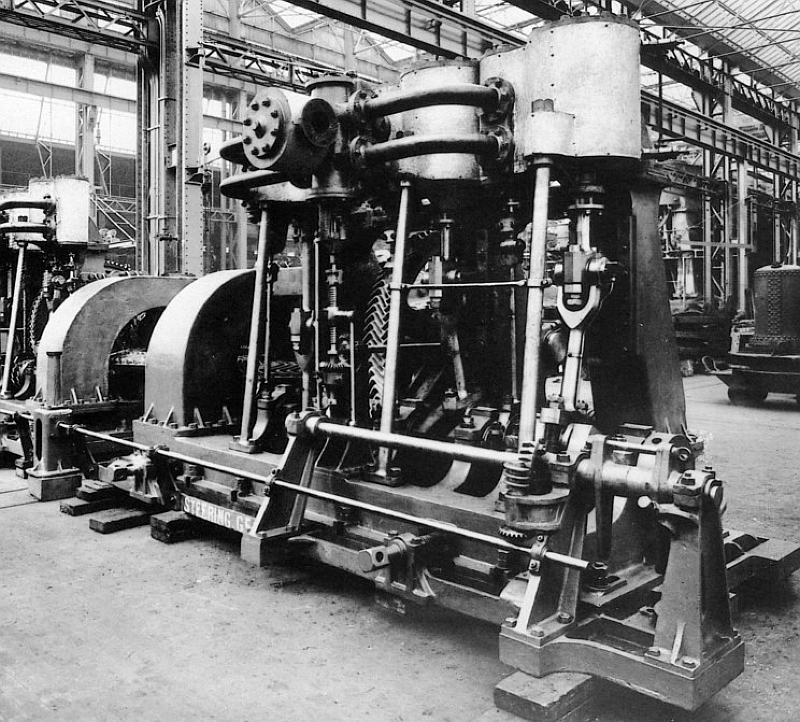

is the rudder’s steering turbine engine

One

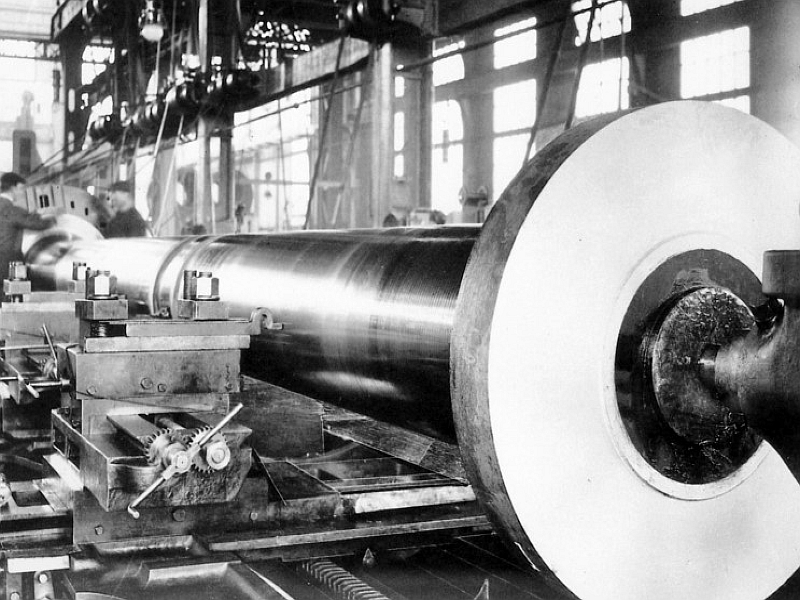

of Britannic’s propeller shafts

Britannic

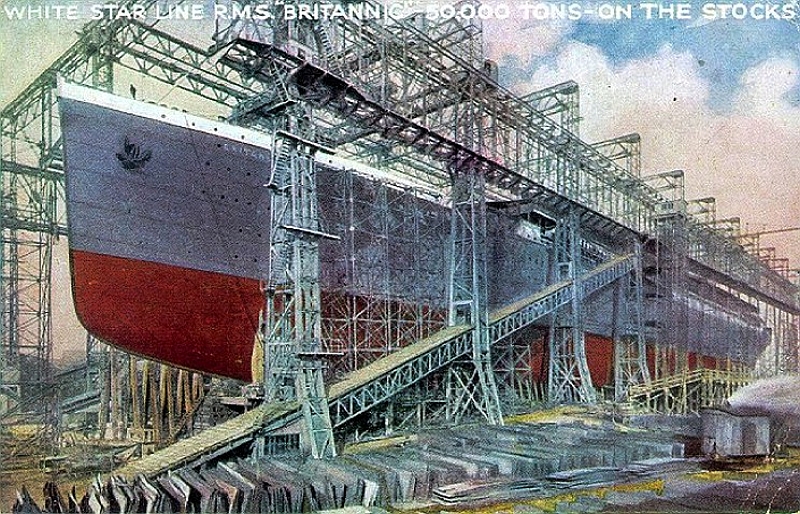

nearing her launch-date as well as a great view of her Gantry!

This

is a rare colourised image

Source unknown

– Please see Photo notice at bottom of page

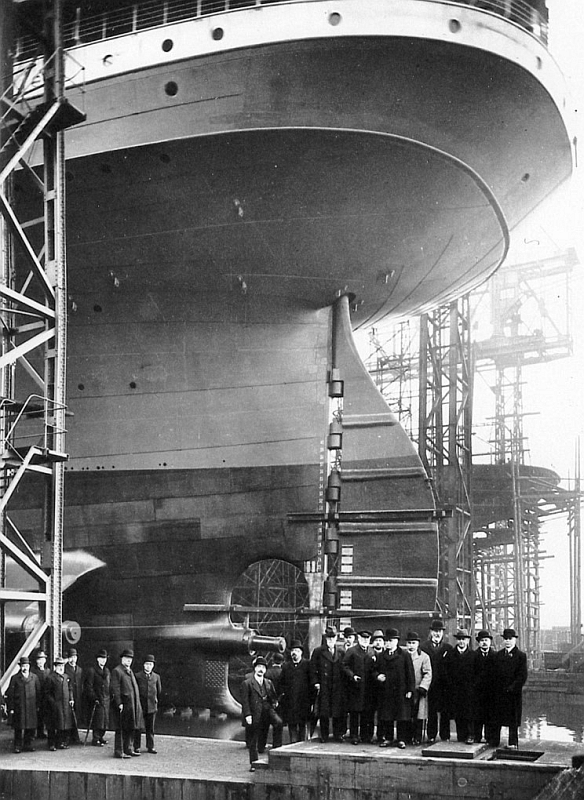

With her building having slowed

down due to the war, but once her hull and the main part of her superstructure

had been completed, except the Bridge and housing and funnels up on Boat Deck,

etc, the Britannic was launched with many White Star dignitaries present on

February 26, 1914, and she was towed to the Harland & Wolff fitting-out

berth to complete the Britannic.

Photographs

of the Launching

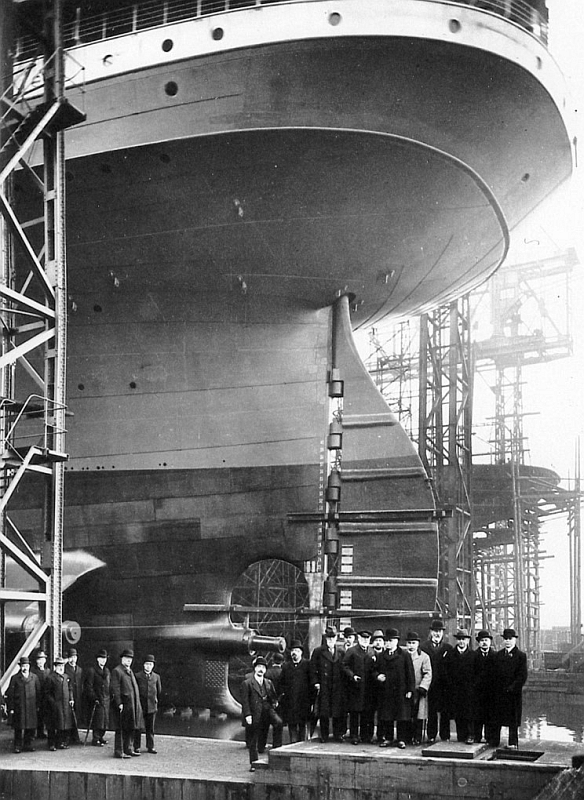

Below

her mighty stern we see a group of dignitaries just prior the launching on

February 26, 1914

An

excellent view as she rolls off the blocks

The great ship is finally afloat

and should be looking forward to a long future – BUT?

With the war having commenced,

the Admiralty began to requisition a large number of ships as armed merchant

cruisers or as troop transport ships. The problem however for the relevant

companies involved that the Admiralty was paying the companies for the use of

their vessels, but the risk of losing a ship during military operations was

considered to be very high. However, the big passenger liners were not taken

for direct military use, mostly because smaller ships were easier to manoeuvre

and operate. During this time, White Star decided to withdraw the RMS Olympic

from service until the danger on the Atlantic had passed, thus the Olympic

returned to Belfast

on November 3, 1914, while the fitting-out on her sister continued slowly.

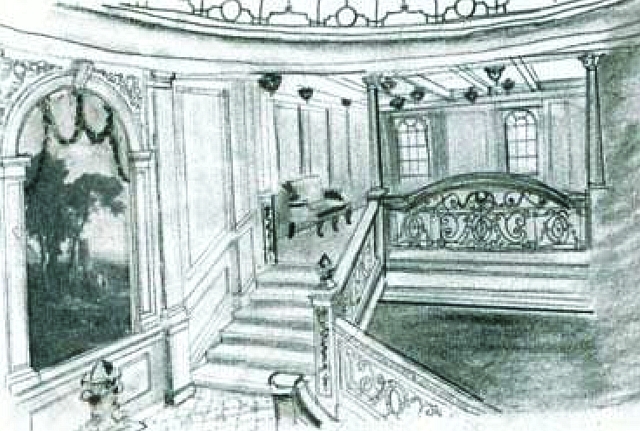

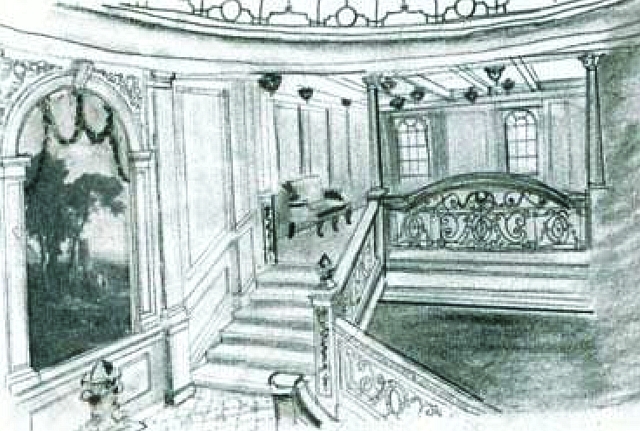

An

impression of Britannic’s First Class Staircase

Sent in by a

supporter but source unknown – Please see Photo notice at bottom of page

A very

rare image of the illustration that became a reality!

Slowly the fitting out of the

Britannic’s interiors were almost completed and she was looking good with

most of the same features of the Olympic, and her First Class Staircase had

another feature as is shown above, rather than a clock, as on the previous

sisters, she had a stunning painting surrounded by timber scrolls and elegant

decorations.

Although the ship was far from ready, but as

far back as in July 2, 1914 White Star Line had announced that the RMS

Britannic would commence her Southampton to New York service in the spring of 1915.

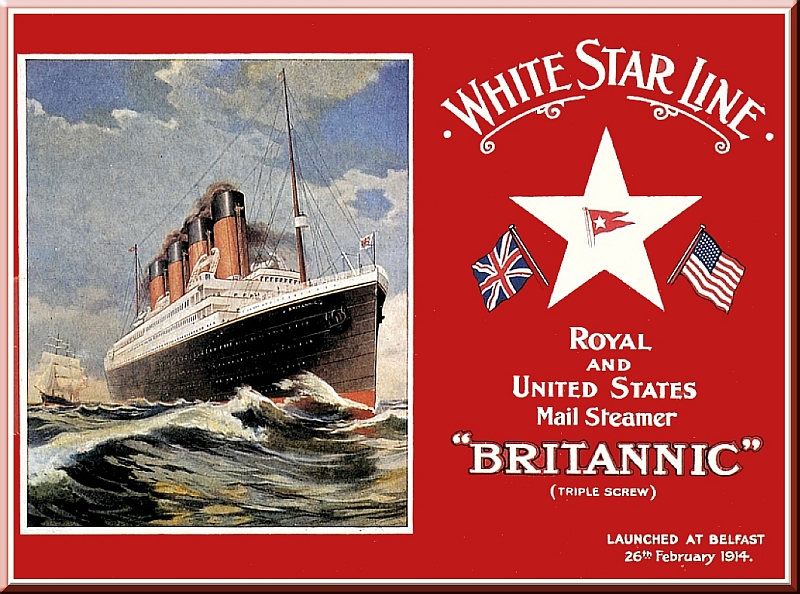

The

official White Star Poster that accompanied the announcement of her commencement

in spring 1915

However, White Star

was soon told that the ship may well be required and be used as a hospital

ship, and thus she was partially prepared for the job before she was even

officially requisitioned. In May 1915, she had her mooring trials of her

engines and she was now fully prepared for an emergency entrance into war

duties with as little as four weeks notice. Tragically it was in that very same

month on May 7, 1915 that the Cunard passenger liner RMS Lusitania was

torpedoed by a U-Boat some 18km from the Irish

coast and Old Head of Kinsale Lighthouse.

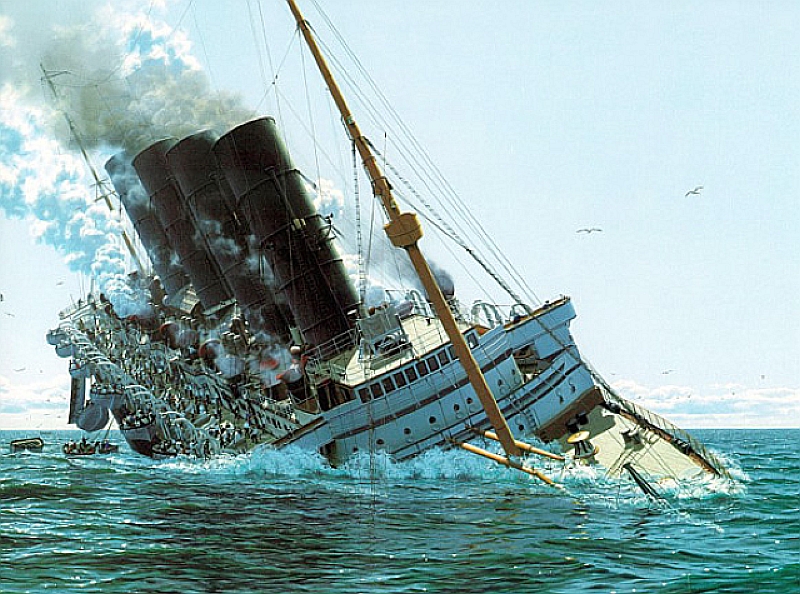

The

tragic final moments of the RMS Lusitania

above is © Copyright by Ken Marschall Visit Ken’s Web

Site at: www.trans-atlanticdesigns.com

German U-Boat number U-20 was under the command of Kapitänleutnant

Walter Schwieger, who was sent to attack British ships around the British

coast, and he was known to attack all kind of ships and he even fired at

neutral ships as he suspected that they may be British in disguise. In an

earlier voyage, he narrowly missed hitting a hospital ship with one of his

torpedoes. Thus his reckless reputation made it more likely for him to

torpedo a British passenger liner, such as the Lusitania. His evil act killed 1,198

innocent lives out of the 1,959 on board the RMS Lusitania with 761 survivors.

The world was stunned to hear about this atrocity, for it was the first time

ever that a passenger ship had been targeted and it was against all wartime

conventions!

With this horrid event having occurred the

Admiralty decided that there was an immediate need for additional and larger

tonnage and that operations would have to be extended into the Eastern Mediterranean and wherever it was needed!

Thus in June 1915, the British Admiralty

decided to requisition larger passenger liners for used as troop transports for

the Gallipoli campaign. The first to depart were the Cunard liners; HMT Mauretania

and HMT Aquitania. As the Gallipoli landings had proved to

be disastrous and the casualties were to say the least massive with countless

losses of Australian, New Zealand and British soldiers, in addition with

countless more wounded as it had been an unbelievable slaughter field, there

was a desperate need for large hospital ships to provide efficient treatments

and to aid in the evacuation of the wounded. For this reason the troopship, HMT

Aquitania would become a hospital ship in August, and the then in storage RMS

Olympic would take over from the Aquitania

and become a trooper from September 1915.

4… From Liner to Hospital Ship:

On November 13, 1915

the Britannic was officially requisitioned to become a hospital ship by the British

Admiralty. Thus as she was still in storage at Belfast, she had to return to

the Harland & Wolff yards and be rapidly made ready as a hospital ship with

facilities for some 3,300 beds, and her luxury fittings and furnishings were

removed and placed into storage, whilst other simpler furnishings were loaded

for use on board.

Senior medical staff such as officers, doctors

and senior registered nurses, etc would be accommodated in First Class

accommodations, whilst the rest would use Second Class and the best of Third

Class accommodations. The huge First Class Dinning Room became the ICU

“Intensive Care Unit”, whilst the adjoining Reception Lounge was

converted into a fully equipped operating theatre.

Public rooms and glazed in decks became large

dormitories for the wounded, and it was also convenient as their location would

always be close to their lifeboat stations should any emergency ever come

about. Thus, the Britannic became a full-scale hospital ship and upon

completion she was able to accommodate just over 3,300 wounded.

During this time she was also repainted in the

official “International Red Cross” livery, being all white with

three large red crosses on each side of her hull, as well as a green band.

Officially her Red Cross designation would give her safety in international

waters.

Here

we see the HMHS Britannic as she was seen in a movie

The Britannic arrived at

Liverpool from Belfast on December 12, which was a very big day for the ship,

for 1: Captain Bartlett, who had been the company’s marine superintendent

in Belfast whilst the Britannic was being built, boarded her on this day; 2:

She was officially commissioned as a hospital ship and given her Pennant Number

G 618 on this day. 3: Under the command of Captain Charles A. Bartlett

the Britannic took on board a comprehensive medical staff. made up of 52

officers and doctors, 101 nurses, 336 orderlies, and 675 male and female

crewmembers (although many crew had already boarded previously), making this a

big day for the ship! During the Britannic’s stay in Liverpool she took

on all her requirements such as food, supplies of various kinds, but most

importantly a massive amount of medical supply.

Captain

of the HMHS Britannic, Captain Charles A. Bartlett

5… HMHS Britannic’s

Career as a Hospital Ship:

Voyage 1: Her Maiden Departure.

December 28, 1915 - HMHS Britannic departed Liverpool

on her maiden departure bound for Mudros located on the Island of Lemnos,

Greece. She made a call at Naples Italy early in

the morning on December 28, where she would load coal and departed in the

afternoon and arrived in Mudros on December 31, where she took on board some

3,300 casualties. On January 3, 1916 she departed bound for Southampton

where she arrived on the 9th.

Here

we see the HMHS Britannic on her maiden departure

Here

we see two nurses at a ward set up along the deck space, during a voyage to

Lemnos or Naples

as it is empty

Voyage 2:

January 2, 1916 – she departed for her second voyage to Mudros and again

stopped at Naples.

However, this time she was held up in Naples

due to the countless casualties based on other ships. It was decided to

transfer thousands of these to the Britannic and she returned to the UK, rather than going on to Greece. She

arrived back in Southampton on February 9.

She remained in Southampton

for well over a month.

Voyage 3:

March 20 – Britannic departed this time for Augusta

in Sicily where she loaded casualties from

another ship and arrived back in Southampton

on April 4.

Having offloaded all casualties in April, she

was anchored off the Cowes, Isle

of Wight and she was used as a floating hospital as there was an

overload of casualties ashore. At the end of her mission there, she sailed for Belfast.

May 8 – Britannic arrived at Harland

& Wolff to be refitted as a passenger liner once again.

June 6 – Britannic is officially

released and returned to White Star Line, but she is laid up,

August 28 – The Britannic is

requisitioned once again by the Admiralty as a hospital ship and she made ready

once more and departs for Southampton.

Voyage 4:

September 24 – she departs Southampton Mudros, arriving in Naples for coal on the

29th. She arrived in Mudros on October 3 and took on board a large number of

casualties as usual. She returned to Southampton

on October 11.

She

is seen here in Naples

loading coal

Here

we see the HMHS Britannic and the HMHS Galeka berthed alongside at Mudros, as

they transfer wounded soldiers and goods

These

smaller hospital ships would do the work in the local areas and transfer their wounded

to the larger ships as they arrive

Voyage 5:

October 20 –

Britannic departs Southampton for a direct

sailing for Mudros. On board she has additional medical personal and a large

stock of medical supplies which are to be used in Malta,

Egypt and in India! She

arrived at Mudros on October 28. Everything is offloaded and departs as soon as

possible with further wounded aboard and returns to Southampton

on November 6.

The

Britannic is looking somewhat worn, but she is a hard working ship!

She

is seen here at Mudros during having offloaded the medical supplies onto barges

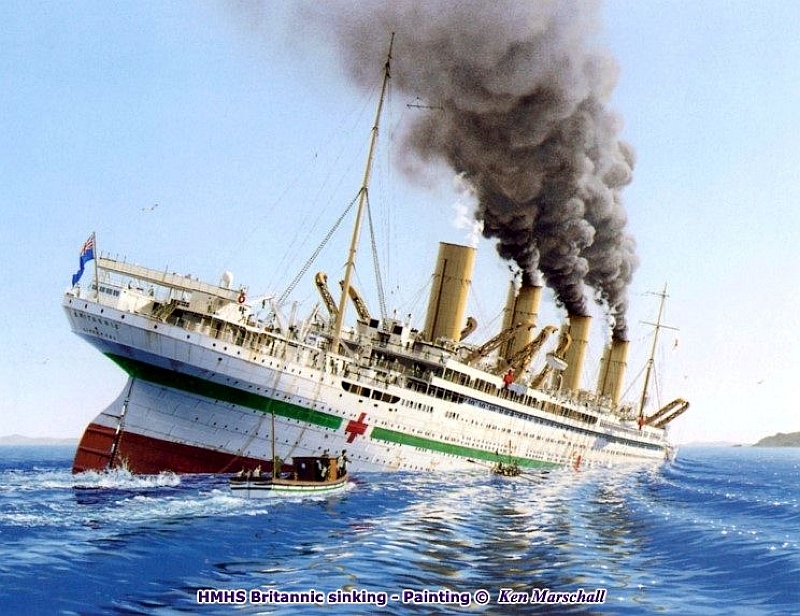

Voyage 6 – Her Final Voyage!

November 12 –

HMHS Britannic departed Southampton with a total of 1,066, being a medical

staff and crew, and she arrived at Naples

around 7 am on November 17, for it was here she would normally load coal.

However rather than departing on time in the

afternoon, she was held up, because of extreme bad weather conditions and she

departed three days late for Lemnos on

November 20. How different her history might have been IF she only been

able to depart on time, for the very next day November 21, 1916 would

be the magnificent Britannic’s very last day afloat!

6… Details of Her Final Days and

Tragic Voyage:

After completing

five successful voyages to the theatre of war and back to England transporting countless of ill and

wounded soldiers and others, the Britannic departed Southampton for Lemnos at

2.23 pm on November 12, 1916 being her sixth voyage to the Mediterranean.

The Britannic passed Gibraltar around midnight

on 15 November, she arrived at Naples at around

7 am on November 17, for Naples

was usually her coaling and water refuelling stop, thus it being the first port

of call on each voyage, except one. However, a storm stopped the ship from

departing until Sunday afternoon the 20th, as there was a break in the weather

and Captain Bartlett decided to take advantage of this quiet spell and sail.

The seas rose up again as soon as the Britannic had left port.

Tuesday November 21, 1916:

The following morning November 21 the storms

had thankfully gone and the seas were calm and Britannia had passed the Strait of Messina in the very early hours and without problems.

Next was Cape Matapan and that was rounded

during the first few hours of the day. Soon the Britannic was steaming at full

speed into the Kea Channel, between Cape

Sounion, which is the southernmost

point of Attica, the prefecture that includes Athens,

and the island

of Kea.

Whilst en-route to pick up patients off the

coast of Greece in the Kea

Channel at Lemnos, Mudros, the Britannic was

rocked without warning by a violent explosion and amazingly this great and

well-built ship sank in just 55 minutes! Here is what happened …

At 8:12 am on

November 21, without any warning there was a very loud explosion and the ship

was thrown instantly off-course by three points (33.75 degrees), whist her bow

rose noticeably and then came back down rapidly. During this, she suffered

severe shaking and vibrations along her hull. The actual cause was as yet

unknown, was it a torpedo from an enemy submarine or a mine. However as it

turned out, the ship had apparently hit a mine that had been laid that same

week by the U-Boat - U-73.

The reaction on board and those who were

having breakfast in the dining room was obviously immediate; doctors and nurses

departed for their posts. But as human nature is, not everyone reacted in the

same manner. Obviously further aft the power of the explosion was far less and

most thought the ship had hit an object, or even a smaller boat.

Captain Bartlett and Chief Officer Hume were

on the bridge at the time and the gravity of the situation very evident to

them. The explosion was on the starboard side, between holds two and three. The

force of the explosion damaged the watertight bulkhead between hold one and the

forepeak, thus the first four watertight compartments were filling rapidly with

water. In addition, the firemen’s tunnel that connected the

firemen’s quarters in the bow to boiler room number six was seriously

damaged, and therefore water would be flowing right into that boiler room.

Captain Bartlett ordered the watertight doors

closed immediately, sent a distress signal and ordered the crew to prepare the

lifeboats. Thankfully aboard Britannic there were sufficient lifeboats for all

on board, and even more if needed! Along with the damaged watertight door of

the firemen's tunnel, for some reason the watertight door between boiler rooms

six and five failed to close properly. Water was flowing further aft into

boiler room five and thus the great ship Britannic was quickly reaching her

flooding limit. She could stay afloat whilst motionless with her first six

watertight compartments flooded. There were five watertight bulkheads rising

all the way up to B-deck. Those measures had been taken after the Titanic

disaster. The next crucial bulkhead between boiler rooms five and four and its

door were undamaged and should have guaranteed the survival of the ship.

However, there were open portholes along the lower decks, which tilted

underwater within minutes of the explosion. The nurses had opened most of those

portholes to ventilate the wards. As the ship's list increased, water reached

this level and began to enter aft from the bulkhead between boiler rooms five

and four. With more than six compartments flooded, the Britannic would not be

able to stay afloat.

At 8.24 am the

Captain decided on a desperate measure and he ordered to restart the engines

and make an attempt to beach the ship.

At 8:25 am

lifeboats are still being filled but they are not allowed to leave. Yet without

authority some boats leave the ship from the portside and because of the list,

they are scraping along the ship's side. In addition as the ship is underway

again heading for the beach, the propellers are turning fast, and they are

breaking the surface by now.

At 8:35 am

things had increasingly become much worse and Captain Bartlett decided that

there was little time left, thus he brought the ship to a full halt and orders

“abandon ship” and all lifeboats to be lowered and sent away.

However, he is unaware that just a few minutes prior to his order that two unauthorised

lifeboats left the ship and were drawn into the portside propeller killing most

of the occupants, while a third one has a narrow escape as the propeller stops

seconds before impact. It is now

8:50 am whilst laying

idle the Britannic is settling more slowly and most of the lifeboats manage to

escape without further problems. Bartlett

decides to try again to beach the ship and restarts the engines. Britannic's

sinking rate increases again and water is soon reported forward on D-Deck.

9:00 am -

Captain Bartlett is informed of the water on D-Deck he gives the order to

abandon ship and Britannic’s horn is blown for the last time. Water has

by now reached the bridge and Assistant Commander Dyke informs his Captain that

all have left the ship. Dyke, Chief Engineer Fleming and Bartlett simply walk

towards the sea near the forward gantry davits. Shortly after their escape

funnel No.3 collapses.

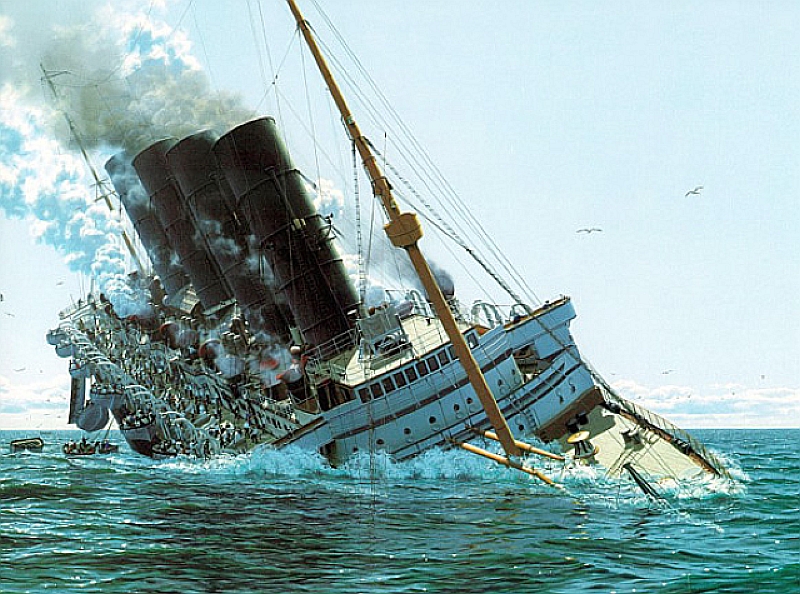

9:04 am - as

the water is now 119 meters deep, Britannic's bow hits the bottom whilst the

stern is still above the surface. The last few men who were below decks not

seen by Assistant Commander Dyke have by now left the ship. Fifth Officer

Fielding estimates the stern rising some 150 feet into the air.

9:06 am - with

all her funnels detached, Britannic finally completes her starboard roll,

causing heavy damage to the forward bow area.

9:07 am –

The once majestic RMS – HMHS Britannic slips beneath the surface of the

clam sea landing goes down to her final resting place!

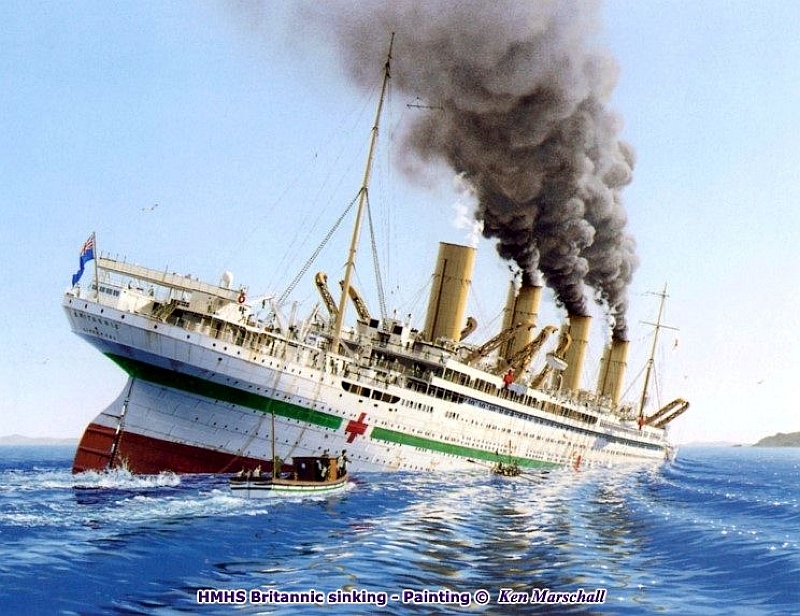

Image

above is © Copyright by Ken Marschall Visit Ken’s Web Site

at: www.trans-atlanticdesigns.com

Miss Violet Jessop who amazingly was also one of the survivors of the RMS Titanic, as

well as HMT Olympic, when the HMS Hawke collided with her, described

Britannic’s last seconds as follows:

“She dipped her head a little, then a

little lower and still lower. All the deck machinery fell into the sea like a

child's toys. Then she took a fearful plunge, her stern rearing hundreds of

feet into the air until with a final roar, she disappeared into the depths, the

noise of her going resounding through the water with undreamt-of violence....”

What is so amazing

is that all this occurred in calm weather and within sight of land and she sunk

in just 55 minutes, and having 1,066 crew and medical staff aboard, there were

only 30 deaths, and then these deaths were sadly related to those who were in

the two unauthorised lifeboats!

As I already indicated, the main cause of

deaths in this tragedy was, in fact, the premature lowering of two lifeboats,

which was done whilst the ship was moving in an attempt to beach her,

these two lifeboats were lowered before the official “abandon ship”

order was given and they were tragically dragged in by the powerful propellers

and destroyed causing deaths and injury to others. Eventually, the beaching

attempt was abandoned and the rest of the crew escaped to the lifeboats and to

shore. Fortunately, the ship was carrying no patients at the time of the

sinking, and thus the evacuation was made a great deal easier!

Today the cause of the sinking of the

Britannic is universally attributed to a German mine. However over the

years, there have been various theories, 1: that it was a torpedo, or 2: that

it was indeed a mine. Many somehow preferred the idea that it was hit by a

torpedo, because it would have been in violation of the Geneva

Convention. But, there is very little evidence to support the torpedo

theory. In addition it became soon known that German U-Boat U-73

had mined the channel that the Britannic passed only a few weeks prior the

sinking.

In addition, after a period of speculation the

mine theory was confirmed by U-73's commander Captain Siess’ log, that he

had only laid mines. And then there is the fact that the Union Castle

Line’s Breamar

Castle, also struck a mine in the same

region just two days later!

7… The Rescue of those on board

Britannic:

The first vessel to arrive on the

scene had some Greek fishermen from Kea on their Caïque, who picked up many men

from the water. One of them, Francesco Psilas, was later paid UK£4 pound by

the Admiralty for his services.

At 10.00 am – the HMS Scourge sighted the first lifeboats and ten minutes later stopped and

picked up 339 survivors.

HMS Heroic had

arrived some minutes earlier and picked up 494. Some 150 had made it to

Korissia, being a community on Kea, where surviving doctors and nurses from the

Britannic were trying to save the horribly mutilated men, using aprons and

pieces of lifebelts to make dressings. A little barren quayside served as their

operating room. Although the motor launches were quick to transport the wounded

to Korissia, the first lifeboat arrived there some two hours later because of

the strong current and their heavy load. It was the lifeboat of Sixth Officer

Welch and the unknown Officer. The latter was able to speak some French and

managed to talk with one of the local villagers, obtaining some bottles of

brandy and some bread for the injured.

Here

we see some of the rescued crew on board the HMS Heroic

The inhabitants of Korissia were

deeply moved by the suffering of the wounded. They offered all possible

assistance to the survivors and hosted many of them in their houses while

waiting for the rescue ships. The HMS Scourge and HMS Heroic had no more deck

space to take further survivors and thus they soon departed for Piraeus signalling the

presence of those left at Korissia.

Violet Jessop

approached one of the wounded. “An elderly man, in an RAMC uniform with a

row of ribbons on his breast, lay motionless on the ground. Part of his thigh

was gone and one foot missing; the grey-green hue of his face contrasted with

his fine physique. I took his hand and looked at him. After a long time, he

opened his eyes and said: 'I'm dying'. There seemed nothing to disprove him yet

I involuntarily replied: 'No, you are not going to die, because I've just been

praying for you to live'. He gave me a beautiful smile - That man lived and sang

jolly songs for us on Christmas Day.”

11.45 am HMS Foxhound arrived and after sweeping the area she anchored in the small port

at 1.00 pm to offer medical assistance and took aboard the remaining survivors.

2.00 pm HMS Foresight a light cruiser arrived. The HMS Foxhound departed for Piraeus at 2.15 pm with

more survivors. The Foresight remained to arrange the burial on Kea of Sergeant

W. Sharpe, who had died of his injuries. Another two men died on the Heroic and

one on the French tug Goliath. The three were buried with military honours in

the British cemetery at Piraeus.

The last fatality was G. Honeycott, who died at the Russian

Hospital at Piraeus shortly after the funerals.

Thankfully out of the 1,066 souls on board.

1,036 people were saved, whilst some thirty men lost their lives in the

disaster, but only five were buried. The others were left in the water and

their memory is honoured in memorials in Thessaloniki

and London.

Another twenty-four men were injured. The ship carried no patients. The survivors

were hosted in the warships that were anchored at the port of Piraeus.

However, the nurses and the officers were hosted in separate hotels at

Phaleron. Many Greek citizens and officials were kind enough to attend the

funerals.

8…

Britannic’s Wreck Site:

The wreck of HMHS

Britannic is in Aegean Sea, some 2 miles northwest of Kea Island, Greece

(37.42N - 24.17E) in about 400 ft (120 m) of water. It was first

discovered and explored by Jacques Cousteau in 1975. The giant liner lies on

her starboard side hiding the impact with the mine. There is a huge hole just

beneath the forward well deck. The bow is attached to the rest of the hull only

by some pieces of the B-deck. This is the result of the massive explosion that

destroyed the entire part of the keel between bulkheads two and three and of

the force of impact with the seabed. The bow is heavily deformed as the ship

hit the seabed before the total length of the 882 feet 9 inches (269 m)

liner was completely submerged, as she sank in a depth of only 400 feet

(120 m) of water. Despite this, the crew's quarters in the forecastle were

found to be in good shape with many details still visible.

The Britannic seen on the floor of the ocean

Image above is ©

Copyright by Ken Marschall Visit Ken’s Web Site at: www.trans-atlanticdesigns.com

The holds were found

empty. The forecastle machinery and the two cargo cranes in the forward well

deck are still there and are well preserved. The foremast is bent and lies on

the sea floor near the wreck with the crow's nest still attached on it. The

bell was not found. Funnel #1 was found a few metres from the Boat Deck. The

other three funnels were found in the debris field (located off the stern). The

wreck lies in shallow enough water that scuba divers trained in technical

diving can explore it, but it is listed as a British war grave and any

expedition must be approved by both the British and Greek governments.

RMS

Britannic Specifications as a Passenger Liner:

Built

by: Harland & Wolff, Belfast.

Yard: 401.

Laid down: November 30, 1911.

Launched: February 26, 1914.

During fit-out: Converted as a Hospital Ship.

Completed: December 8, 1915.

Maiden Voyage: December 23, 1915 for the British

Admiralty.

Tonnage: 48,158 GRT (Gross Registered

Tons).

Displacement: 52,310 tons

at 34.7ft.

Length: 259.7m - 903ft.

Width: 28.65m - 94ft.

Draught: 34.6ft

– 10.54.

Engines: 2 four

cylinder triple expansion (outside props).

1

Parsons low pressure steam turbine (center prop)

Boilers: 24 Double ended – 5

Single ended – coal fired.

Funnels: 4.

Masts: 2.

Screws: Triple - 51,000 IHP.

Shafts: 3

Speed: 21 knots service speed

– 22.5 knots max.

Passengers: 790 First Class. 836 Second Class.

953 Third Class.

Officers & Crew: 930.

As

HMHS Britannic – Hospital Ship:

Wounded: 3,300.

Medical staff: 437.

Officers & Crew: 724.

Final Voyage: 1,066 persons on board.

**************************************************

Let

us Remember the Britannic and NEVER Forget

Her!

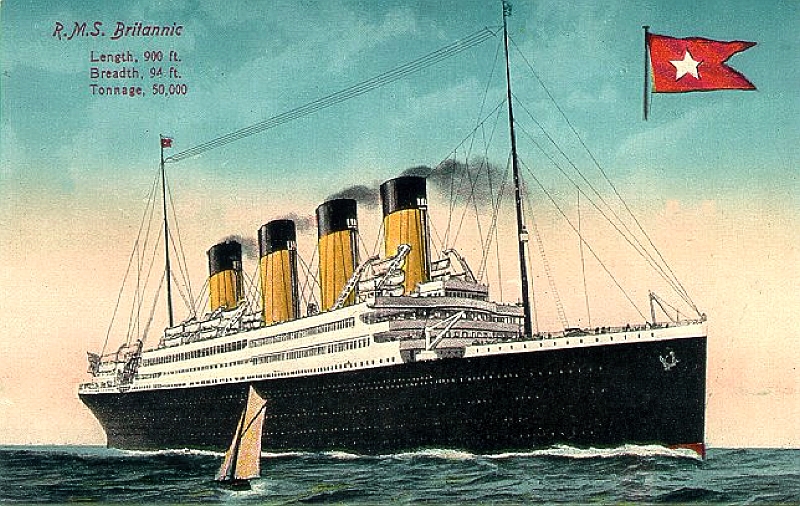

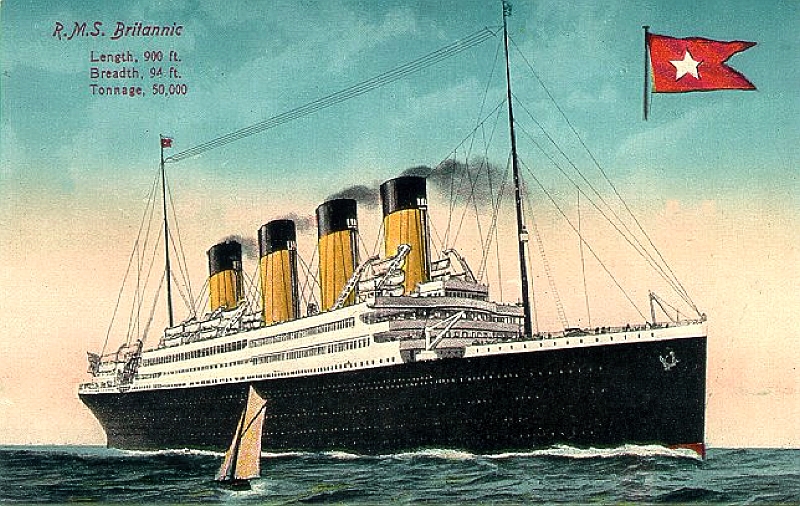

This is how we should really remember this truly

great ship as she would have looked like had she sailed the Atlantic!

RMS Britannic was a superbly built liner and

she would have been great if she would have been allowed to sail on for many

more years, like her successful sister the RMS Olympic for many years, but

instead the elegant HMHS Britannic sailed and cared for tens of thousands of

wounded soldiers for just under eleven months and then

she fell victim to a German laid mine.

****************************

Also

read my two page feature on the RMS Olympic

- “Old Reliable”

& the RMS Titanic!

RMS Olympic … Olympics’

History Page & Interior Photographs - in service

1911 to 1935.

RMS Titanic … Two Page Titanic feature with photographs.

HMHS Britannic … The Britannic story -

in service 1915 to 1916 - (This Page).

“Blue Water Liners sailing to the distant shores.

I watched them come, I watched them go and I watched them die.”

****************************

Visit our ssMaritime - Main INDEX

Where

you will discover over 700 Classic Passenger & Passenger-Cargo Liners!

ssMaritime.com & ssMaritime.net

Where

the ships of the past make history

&

the 1914 built MV Doulos Story

Please

Note: ssmaritime and associated sites are 100%

non-commercial and the author does not seek funding or favours and never have

and never will.

Photographs

on ssmaritime and associate pages are either by the author or from the

author’s private collection. In addition there are some images and

photographs that have been provided by Shipping Companies or private

photographers or collectors. Credit is given to all contributors, however,

there are some photographs provided to me without details regarding the

photographer or owner concerned. Therefore, I hereby invite if owners of these

images would be so kind to make them-selves known to me (my email address can

be found at the bottom of the page on www.ssmaritime.com), in order that due credit may be given.

ssMaritime is owned &

© Copyright by Reuben Goossens - All Rights Reserved